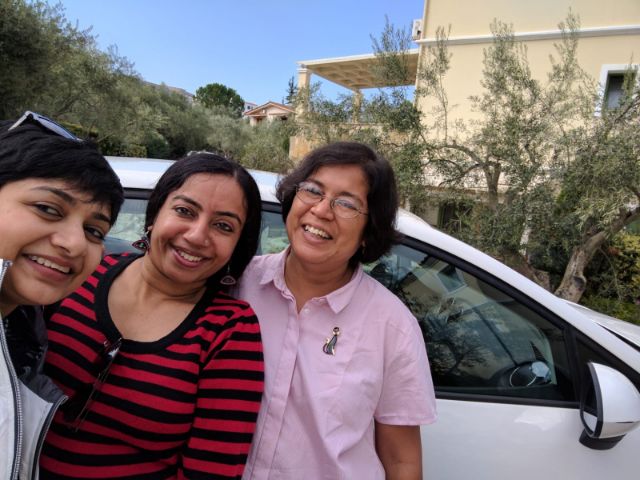

Travel shifts your perspective. But what changes you more is a journey with your soul sisters. I learnt this on a road trip in Greece, with Sowmya and Anamika, my friends and partners on many adventures.

Everything started with my newly issued passport and a decision to put it to good use. By then, Sowmya had also been in the U.S. for a decade—just as long as it had been since we had last hit the road together. We decided it was time for us to strap on our backpacks again.

Countless emails, Google searches, late night coffees and hours on Airbnb later, a plan was made. Destination Greece it was. At least so we thought, till Sowmya could not board her flight when she discovered she needed a transit visa to pass through Canada. But we persevered, she rescheduled her arrival by a couple of hours, and destination Greece it remained.

Nafplio, here we come

That was how three of us wound up stranded outside Athens International Airport on a windy November night. By this time, we should have boarded a bus hours ago and arrived at the seaport town of Nafplio. Now, last-minute changes were needed to our plan.

We ended up in a car rented from Hertz, with Sowmya, who was most suited to driving on the right side of the road in the driver’s seat. We finally arrived in Nafplio after midnight—tired, excited, and quite lost. But our host Theo saved the day. He drove to meet us, and we followed him home.

The next morning, we woke up ready to discover Greece like the locals. Our first stop—the neighborhood supermarket, where we stocked for the trip ahead. Outside, the obvious sign of being in a city by the sea was Nafplio’s spectacular pier, where locals spent many leisurely hours fishing.

But before you dismiss this as a quaint fishing village, Nafplio was in fact the first capital of the modern Greek state before Athens took over in 1834. A city of ancient origins steeped in legend, it is named after Nafplios, son of the Greek God of the Sea, Earthquakes, and Horses Poseidon. Also believed to be the home of the Trojan hero Palamidis, Nafplio was a bustling city of the Neolithic period, before it fell into disuse during the Classical period of Greek’s history. It was later resurrected by the Venetians, who built the Palamidi Fortress and its accompanying castle. Both stand to this day. Later, the city would also be handed over to the Turks, who controlled it for 100 years.

My most special memory here will remain our drive up to the fortress, from where we looked down at a faintly pink-hued vision of Nafplio, idyllic in the distance. Every city has a distinctive view or a moment, which cannot be experienced anywhere else in the world. The view of Nafplio flanked by the sea, seen from the Palamidi Fortress, was such a moment for me. In its long history, the city had made friends and foes. Yet while the Trojans, Spartans, Franks, Venetians, and Turks had fallen. Nafplio still stood, a modern Greek town.

Ancient Epidaurus

But in this part of Greece strewn with myths, there were many old stories like the one of Nafplio, and we were eager to find them. So, we followed the road to the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus in a Greek city by the same name. Reputed to be the birthplace of Apollo’s son Asclepius the Healer, Epidaurus was the center of healing of the Classical World. Starting with the cult of Asclepius that flourished in the 6th century BC, Epidaurus would finally evolve into a Christian healing center by the 5th century AD. Even when old ways of worship ceased, the reputation of Epidaurus endured.

The success of a town is best expressed in the greatness of its monuments. This is also true of the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, among the most perfect examples of Greek acoustics and aesthetics. I sat in the topmost corner of this structure and looking down over the vast space ready to host 14,000 spectators.

On stage, a tour guide demonstrated the theatre’s acoustics to her group and showed them how sound carried. She had made her point. Sitting at the topmost point, I heard every word.

Mycenae and the legend of Helen

On day two, we chased another ancient legend. This time we drove into Mycenean territory, in hot pursuit of Helen of Troy. But there is more to Mycenae than Helen. Beginning from the second millennium BC, Mycenae was one of the great seats of the Greek civilization, dominating southern Greece, Crete, the Cyclades and southwest Anatolia. If legend is to be believed, Helen was the Queen of Mycenae, married to its King Menelaus. It was from this city she eloped with Paris, seeking her final refuge in Troy.

Nothing remains of this past now, except a museum and scattered ruins on a hill. But as sat for some time on its highest peak, which had once been its citadel, we could see how this unique vantage point made it a place where an advanced civilization thrived thousands of years before the birth of Christ. In the soft breeze was the melancholic pathos of a civilization that had long since breathed its last.

Later, on the drive back home, we stopped at a Turkish café for dinner. As the delicious strains of the Bağlama filled the air, we took in the different cultures coalescing in one space, making it home.

Sunrise at Monemvasia.

With the legends of Mycenae behind us, day three was for the tiny island of Monemvasia. What makes this island unique is its other identity of a medieval fortress. Like Nafplio, it has had periods of Byzantine, Venetian, and Ottoman rule, all of which are reflected in its winding alleys and architecture.

A day needs to be devoted to the city and its fortress, which is a medieval delight. You can even rent a room in one of the many hotels in the fortress for a night. But what I remember most from Monemvasia is its breathtaking sunrise. It was perhaps on a Greek island like this one where a medieval artist had his first sighting of the God rays and then resonated it in his art. I saw it too. But I am not uncertain whether my lens captured the complete magnificence of the moment.

The monastery of Mystras

As the sunrise settled in, there were decisions to be made on day four. Anamika was drawn to the fortress of Monemvasia, but Sowmya and I still wanted to return to a medieval monastery town we had passed on our way to Monemvasia. Finally, we dropped Anamika off at the fortress, and returned to the monastery town Mystras.

Along the way, Sowmya and I drove by the legendary city of Sparta. Its modern demeanor has little to root it in history. Only its name remained, a tribute to its legacy. But like the English word it inspired, the “spartan” inhabitants of this city built no monuments. Their impact on the ancient world was huge, but their imprint small. So, when they disappeared, the only trace they left was deeply embedded in memory and history.

The town of Mystras had risen on the ruins of Sparta. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, it emerged as the capital of Morea in the Byzantine Empire. Unlike the ancient civilization of Mycenae, the younger Mystras still stands, and has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. We spent our day making our way to the city summit, navigating our way through its fortress, palace, churches, and monasteries, all immersed in the rich Byzantine influence of art and architecture. Just hours from Mycenae, here we found the first signs of how Christian influences changed Greece forever. Later, sitting in a splendid Byzantine shrine at the summit, in the sun’s last rays, I marveled at how ancient civilizations had clashed here for dominance, leaving behind a strange, new world.

I will never really know what we missed on the path not taken to the fortress at Monemvasia, but I know that my heart was blessed by Mystras, just as Monemvasia had delighted Anamika. Later in the evening, three exhausted but content travelers sat down over souvlakia and ouzo in a Monemvasia eating house to recount and relive their glorious exploits of the day.

The long and winding path to Corinth

With Mystras and Monemvasia behind us on day five, we made our way to Corinth, following the road back to Athens. At many moments I was struck by the beauty of the landscape, but this was the most intense on the long drive to Corinth. There are indeed few experiences of Greece that can match the magnificence of a road trip.

As we approached Ancient Corinth, the first thing I noticed in the distance was the blueness of the sea. If Nafplio was a pink city, the color of Corinth was blue. Perhaps made famous to the modern western world by the writings of the Christian apostle Paul, Corinth had in fact been a city even before 3000 BC. But not enough is known of the ancient civilizations that flourished here. Most architectural ruins relate to the Christian period when Corinth was also the administrative capital of the Roman province of Achaea.

It was at Corinth, just 78 kilometers from Athens, where I had my first sighting of the Corinthian pillars, now synonymous with Greece, and made famous in architecture across the world by the British Empire. Yet my most significant image remains the long, winding road to the citadel of Ancient Corinth. Nothing remains of the old city, as it was destroyed in the catastrophic earthquake of 1858. Only two shrines had been renovated to give us a glimpse into how early Christians prayed here. But in the untamed, raw beauty of the landscape, I saw how the Greeks turned the treacherous terrain into their strongest defence and also experienced the resilience of their lives. If sunrise at Monemvasia was unforgettable, sunset at Corinth still lingers on as well.

Almost reluctantly, we were back on the road to Athens. Before we knew it, we had arrived at the Athens International Airport, and we turned our car in. With our road trip behind us, we commuted like modern Athenians in Greece. We got onto the metro to find our apartment in the city’s suburbs.

The Acropolis

We knew we were in Athens not only by the signboards, but also because homes were smaller, and attention spans shorter here. It was big city life in all its chaotic energy, and we settled in quickly.

Still, we had seen many wonders on the road, but nothing quite matched my first vision of the Acropolis of Athens. Even though I was seeing it for the second time.

Most ancient cities, like Corinth and Mycenae, had an acropolis or citadel, fortifying the upper part of the city. It was here that citizens flocked to protect themselves when cities were attacked. But none of these had the stature of the citadel at Athens. To this alone is given the title the Acropolis of Athens. There are citadels and there is the Acropolis.

The special significance of the Acropolis is not without reason. It was the heart of ancient Athens, and it continues to tower over the modern city in resplendent white limestones, defining its character as it has done for close to 2,500 years. The most famous temples of the old world were built here, amongst them The Parthenon, The Temple of Athena Nike, and The Erechtheion. Yet the most distinguishing structure remains The Parthenon, dedicated to the Greek Goddess of War Athena, who also gave the city her name.

Great monuments rose to match the Acropolis. Amongst them, the Temple of Olympian Zeus, the Ancient Agora, the Temple of Hephaestus, the Roman Agora, and Hadrian’s Library. Today, at the foothills of the foothills of the citadel, the Acropolis Museum rubs shoulders with the Theatre of Dionysus, which is a stone’s throw away from the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. Elsewhere, the colorful flea market of Monastiraki, dotted with Byzantine shrines, is now a vibrant connecting thread between these ancient structures. All these only elevate the grandeur of the Acropolis and give modern day Athens its distinctive character.

So, we sat back by the Monastiraki market later on that chill November night, with wine and many souvlakia, comfortable in conversation and silence, enjoying the wonder that is Athens.

An encounter with the Oracle of Delphi

Yet like seasoned travelers, we had saved the best for the last. So, on the penultimate day of our nine-day trip, we embarked on a final adventure. We set off on a bus ride to Delphi.

If Athens was the power center of ancient Greece and Epidaurus was the place it turned for healing, Delphi was its spiritual center. No important decision was taken without consulting the Oracle of Delphi. In the precincts of this revered space, the Greeks also raised a temple to the Greek God of Light, Knowledge and Harmony Apollo. It was also to Delphi the Greeks turned to celebrate the Pythian Games every four years, a pre-cursor to the Olympics.

While the remains of Apollo’s shrine and the Panhellenic Sanctuary are spectacular, it is the sighting of the Delphi Tholos that has an “other worldly” quality. As one looks down on a circular arrangement of stones that seem to be set almost at the edge of the universe, it seems inevitable for Delphi to have been known known as the omphalos (navel) or the center of the world.

On the road back to Athens, I also thought of how the center of my world had shifted in the last week. We had seen much together over the last nine days. Many things had made this possible. Sometimes, in travel as in life, it pays to go against the grain. Our trip to Greece was so much more rewarding because we traveled in a non-touristic season, interspersing our journey with little gems off the beaten track. Now, locals had more time to talk to us at each of our stops and we experienced every site we visited completely. It was also a wise decision to shun the convenience of travel groups and instead take the more uncertain path of charting out our route with like-minded spirits. It paid to plan, but we also had to accept the universe often has a way of thwarting our best laid plans. That is usually the start of a great adventure, like the one we had.